Themes of Contemporary Art Visual Art After 1980 Audiobook

| Wyndham Lewis | |

|---|---|

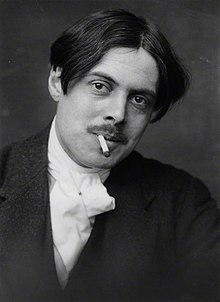

Lewis in 1913 | |

| Built-in | Percy Wyndham Lewis (1882-11-eighteen)18 November 1882 Amherst, Nova Scotia, Canada |

| Died | 7 March 1957(1957-03-07) (aged 74) London, England, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Slade School of Fine Art, University College London |

| Known for | Painting, poetry, literature, criticism |

| Movement | Vorticism |

| Spouse(s) | Gladys Anne Hoskins (1900–1979) |

Percy Wyndham Lewis (18 Nov 1882 – 7 March 1957) was a British writer, painter and critic. He was a co-founder of the Vorticist movement in fine art and edited BLAST, the literary magazine of the Vorticists.[1]

His novels include Tarr (1918) and The Human Age trilogy, composed of The Childermass (1928), Monstre Gai (1955) and Malign Fiesta (1955). A quaternary volume, titled The Trial of Man, was unfinished at the time of his expiry. He also wrote two autobiographical volumes: Blasting and Bombardiering (1937) and Rude Assignment: A Narrative of my Career Upwardly-to-Engagement (1950).

Biography [edit]

Early life [edit]

Lewis was built-in on 18 November 1882, reputedly on his male parent'due south yacht off the Canadian province of Nova Scotia.[2] His English female parent, Anne Stuart Lewis (née Prickett), and American father, Charles Edward Lewis, separated well-nigh 1893.[2] His mother subsequently returned to England. Lewis was educated in England at Rugby School and then Slade School of Fine Art, University Higher London. He spent most of the 1900s travelling around Europe and studying fine art in Paris. While in Paris, he attended lectures by Henri Bergson on process philosophy.

Early on piece of work and development of Vorticism (1908–1915) [edit]

Wyndham Lewis, 1912, The Dancers

Wyndham Lewis, c.1914–15, Workshop (Tate, London)

In 1908, Lewis moved to London, where he would reside for much of his life. In 1909, he published his outset work, accounts of his travels in Brittany, in Ford Madox Ford's The English Review. He was a founding fellow member of the Camden Town Group, which brought him into shut contact with the Bloomsbury Group, particularly Roger Fry and Clive Bell, with whom he soon brutal out.

In 1912, Lewis exhibited his work at the second Postimpressionist exhibition: Cubo-Futurist illustrations to Timon of Athens and iii major oil paintings. In 1912, he was commissioned to produce a decorative mural, a driblet pall, and more designs for The Cave of the Golden Calf, an avant-garde cabaret and nightclub on Heddon Street.[2] [3]

From 1913 to 1915, Lewis developed the fashion of geometric brainchild for which he is best known today, which his friend Ezra Pound dubbed "Vorticism". Lewis sought to combine the stiff construction of Cubism, which he constitute was not "live", with the liveliness of Futurist art, which lacked structure. The combination was a strikingly dramatic critique of modernity. In his early on visual works, Lewis may take been influenced by Bergson's procedure philosophy. Though he was subsequently savagely critical of Bergson, he admitted in a letter to Theodore Weiss (19 April 1949) that he "began by embracing his evolutionary organisation." Nietzsche was an every bit of import influence.

Lewis had a brief tenure at Roger Fry's Omega Workshops, but left after a quarrel with Fry over a commission to provide wall decorations for the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition, which Lewis believed Fry had misappropriated. He and several other Omega artists started a competing workshop called the Rebel Art Middle. The Eye operated for but four months, but it gave nascence to the Vorticist group and its publication, Boom.[4] In Smash, Lewis formally expounded the Vorticist aesthetic in a manifesto, distinguishing it from other advanced practices. He also wrote and published a play, Enemy of the Stars. It is a proto-absurdist, Expressionist drama. Lewis scholar Melania Terrazas identifies it as a forerunner to the plays of Samuel Beckett.[v]

World War I (1915–1918) [edit]

In 1915, the Vorticists held their merely U.K. exhibition before the movement bankrupt up, largely as a upshot of World War I. Lewis himself was posted to the western front and served as a second lieutenant in the Royal Artillery. Much of his time was spent in Forward Observation Posts looking downwardly at patently deserted High german lines, registering targets and calling down fire from batteries massed around the rim of the Ypres Salient. He made vivid accounts of narrow misses and deadly artillery duels.[vi]

Afterward the 3rd Battle of Ypres, Lewis was appointed an official war artist for both the Canadian and British governments. For the Canadians, he painted A Canadian Gun-pit (1918) from sketches made on Vimy Ridge. For the British, he painted one of his all-time-known works, A Battery Shelled (1919), cartoon on his own feel at Ypres.[vii] Lewis exhibited his war drawings and another paintings of the war in an exhibition, "Guns", in 1918.

Although the Vorticist group broke upward after the war, Lewis's patron, John Quinn, organized a Vorticist exhibition at the Penguin Guild in New York in 1917. His first novel, Tarr, was serialized in The Egoist during 1916–17 and published in volume grade in 1918. It is widely regarded as 1 of the key modernist texts.[8]

Lewis later documented his experiences and opinions of this period of his life in the autobiographical Blasting and Bombardiering (1937), which covered his life up to 1926.

Tyros and writing (1918–1929) [edit]

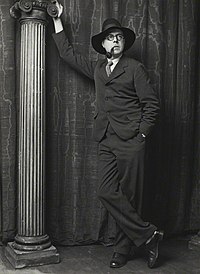

Mr Wyndham Lewis as a Tyro, self-portrait, 1921

Later on the state of war, Lewis resumed his career as a painter with a major exhibition, Tyros and Portraits, at the Leicester Galleries in 1921. "Tyros" were satirical caricatures intended to annotate on the civilization of the "new epoch" that succeeded the Kickoff World State of war. A Reading of Ovid and Mr Wyndham Lewis equally a Tyro are the only surviving oil paintings from this serial. Lewis besides launched his second magazine, The Tyro, of which there were only two issues. The second (1922) contained an important statement of Lewis's visual aesthetic: "Essay on the Objective of Plastic Art in our Fourth dimension".[9] Information technology was during the early 1920s that he perfected his incisive draughtsmanship.

Past the late 1920s, he concentrated on writing. He launched even so another mag, The Enemy (1927–1929), largely written by himself and declaring its belligerent disquisitional stance in its title. The magazine and other theoretical and critical works he published from 1926 to 1929 mark a deliberate separation from the avant-garde and his previous associates. He believed that their work failed to show sufficient critical awareness of those ideologies that worked against truly revolutionary change in the West, and therefore became a vehicle for these pernicious ideologies.[ citation needed ] His major theoretical and cultural statement from this catamenia is The Fine art of Being Ruled (1926).

Fourth dimension and Western Man (1927) is a cultural and philosophical give-and-take that includes penetrating critiques of James Joyce, Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound that are still read. Lewis also attacked the process philosophy of Bergson, Samuel Alexander, Alfred N Whitehead, and others. By 1931 he was advocating the fine art of ancient Arab republic of egypt as impossible to surpass.[ten]

Fiction and political writing (1930–1936) [edit]

In 1930 Lewis published The Apes of God, a biting satirical attack on the London literary scene, including a long affiliate caricaturing the Sitwell family, which may have harmed his position in the literary world.[ citation needed ] In 1937 he published The Revenge for Love, fix in the period leading up to the Spanish Civil State of war and regarded by many every bit his best novel.[11] Information technology is strongly disquisitional of communist activity in Spain and presents English language intellectual boyfriend travellers as deluded.

Despite serious disease necessitating several operations, he was very productive equally a critic and painter. He produced a book of poems, One-Way Vocal, in 1933, and a revised version of Enemy of the Stars. An important volume of disquisitional essays too belongs to this period: Men without Art (1934). It grew out of a defence of Lewis's satirical practice in The Apes of God and puts forward a theory of 'non-moral', or metaphysical, satire. The book is probably all-time remembered for one of the first commentaries on Faulkner and a famous essay on Hemingway.

Return to painting (1936–1941) [edit]

Subsequently becoming better known for his writing than his painting in the 1920s and early 1930s, he returned to more than concentrated work on visual art, and paintings from the 1930s and 1940s constitute some of his all-time-known work. The Surrender of Barcelona (1936–37) makes a significant argument nearly the Castilian Civil War. Information technology was included in an exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in 1937 that Lewis hoped would re-found his reputation as a painter. Afterwards the publication in The Times of a alphabetic character of back up for the exhibition, asking that something from the show exist purchased for the national collection (signed by, amongst others, Stephen Spender, Westward. H. Auden, Geoffrey Grigson, Rebecca Due west, Naomi Mitchison, Henry Moore and Eric Gill) the Tate Gallery bought the painting, Cherry-red Scene. Similar others from the exhibition, it shows an influence from Surrealism and de Chirico's Metaphysical Painting. Lewis was highly disquisitional of the credo of Surrealism, but admired the visual qualities of some Surrealist art.

During this menstruation, Lewis also produced many of his almost well-known portraits, including pictures of Edith Sitwell (1923–1936), T. Southward. Eliot (1938 and 1949), and Ezra Pound (1939). His 1938 portrait of Eliot was rejected by the selection committee of the Royal Academy for their annual exhibition and caused a furore, when Augustus John resigned in protest.

World War Two and North America (1941–1945) [edit]

Lewis spent World War II in the United States and Canada. In 1941, in Toronto, he produced a series of watercolour fantasies centred on themes of creation, crucifixion and bathing.

He grew to appreciate the cosmopolitan and "rootless" nature of the American melting pot, declaring that the greatest advantage of existence American was to have "turned ane'due south back on race, caste, and all that pertains to the rooted state."[12] He praised the contributions of African-Americans to American culture, and regarded Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco as the "best North American artists," predicting that when "the Indian culture of Mexico melts into the swell American mass to the Northward, the Indian volition probably requite it its fine art."[12] He returned to England in 1945.

Afterwards life and incomprehension (1945–1951) [edit]

Past 1951, he was completely blinded by a pituitary tumor that placed pressure on his optic nerve. It concluded his artistic career, but he continued writing until his decease. He published several autobiographical and critical works: Rude Consignment (1950), Rotting Loma (1951), a collection of emblematic short stories about his life in "the capital of a dying empire";[thirteen] [xiv] The Writer and the Absolute (1952), a book of essays on writers including George Orwell, Jean-Paul Sartre and André Malraux; and the semi-autobiographical novel Self Condemned (1954).

The BBC deputed Lewis to complete his 1928 piece of work The Childermass, which was published equally The Human being Age and dramatized for the BBC Third Programme in 1955.[xv] In 1956, the Tate Gallery held a major exhibition of his work, "Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism", in the catalogue to which he declared that "Vorticism, in fact, was what I, personally, did and said at a certain catamenia"—a statement which brought forth a series of "Vortex Pamphlets" from his fellow Smash signatory William Roberts.

Personal life [edit]

From 1918 to 1921, Lewis lived with Iris Barry, with whom he had two children. He is said to have shown fiddling amore for them.[xvi] [17]

In 1930, Lewis married Gladys Anne Hoskins (1900–1979), eighteen years his junior and affectionately known as Froanna. They lived together for x years before marrying and never had children.[18]

Lewis kept Froanna in the background, and many of his friends were unaware of her existence. Information technology seems that Lewis was extraordinarily jealous and protective of his wife, attributable to her youth and beauty. Froanna was patient and caring toward her husband through financial troubles and his frequent illnesses. She was the model for some of Lewis'due south virtually tender and intimate portraits, as well as a number of characters in his fiction. In contrast to his earlier, impersonal portraits, which are purely concerned with external appearance, the portraits of Froanna evidence a preoccupation with her inner life.[xviii]

Ever interested in Roman Catholicism, he never converted.[ citation needed ] He died in 1957. By the time of his death, Lewis had written 40 books in all.

Political views [edit]

In 1931, after a visit to Berlin, Lewis published Hitler (1931), a book presenting Adolf Hitler equally a "human being of peace" whose party-members were threatened by communist street violence. His unpopularity amongst liberals and anti-fascists grew, particularly later on Hitler came to power in 1933.[ citation needed ] Post-obit a second visit to Germany in 1937, Lewis changed his views and began to retract his previous political comments. He recognized the reality of Nazi treatment of Jews subsequently a visit to Berlin in 1937. In 1939, he published an attack on anti-semitism, The Jews, Are They Man?,[a] which was favourably reviewed in The Jewish Chronicle. He too published The Hitler Cult (1939), which firmly revoked his earlier support for Hitler.[ commendation needed ]

Politically, Lewis remained an isolated effigy through the 1930s. In Letter to Lord Byron, W. H. Auden chosen Lewis "that lone old volcano of the Right." Lewis thought there was what he called a "left-wing orthodoxy" in Britain in the 1930s. He believed it was against Great britain'due south self-interest to ally with the Soviet Union, "which the newspapers most of us read tell us has slaughtered out-of-hand, only a few years ago, millions of its meliorate fed citizens, too as its whole majestic family."[xix]

In Anglosaxony: A League that Works (1941), Lewis reflected on his before support for fascism:

Fascism – once I understood it – left me colder than communism. The latter at least pretended, at the start, to accept something to practise with helping the helpless and making the earth a more decent and sensible place. It does get-go from the homo being and his suffering. Whereas fascism glorifies mortality and preaches that human being should model himself upon the wolf.[12]

His sense that America and Canada lacked a British-type form structure had increased his stance of liberal democracy, and in the same pamphlet, Lewis defends liberal democracy's respect for individual freedom against its critics on both the left and right.[12] In America and Catholic Human being (1949), Lewis argued that Franklin Delano Roosevelt had successfully managed to reconcile individual rights with the demands of the state.[12]

Legacy [edit]

In contempo years, there has been renewed critical and biographical involvement in Lewis and his work, and he is now regarded as a major British artist and author of the twentieth century.[20] Rugby Schoolhouse hosted an exhibition of his works in Nov 2007 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his death. The National Portrait Gallery in London held a major retrospective of his portraits in 2008. Two years afterwards, held at the Fundación Juan March (Madrid, Spain), a large exhibition (Wyndham Lewis 1882–1957) featured a comprehensive collection of Lewis's paintings and drawings. As Tom Lubbock pointed out, it was "the retrospective that Britain has never managed to gather.".[21]

In 2010, Oxford Globe Classics published a disquisitional edition of the 1928 text of Tarr, edited by Scott W. Klein of Wake Forest University. The Nasher Museum of Art at Knuckles University held an exhibition entitled "The Vorticists: Insubordinate Artists in London and New York, 1914–18" from 30 September 2010 through two January 2011.[22] The exhibition then travelled to the Peggy Guggenheim Drove, Venice (29 January – 15 May 2011: "I Vorticisti: Artisti ribellia a Londra eastward New York, 1914–1918") and and so to Tate United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland nether the title "The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World" between xiv June and iv September 2011.

Several readings by Lewis are collected on The Enemy Speaks, an audiobook CD published in 2007 and featuring extracts from "1 Way Vocal" and The Apes of God, as well every bit radio talks titled "When John Balderdash Laughs" (1938), "A Crunch of Thought" (1947) and "The Essential Purposes of Art" (1951).[23]

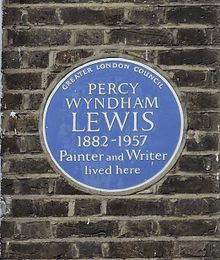

A bluish plaque at present stands on the firm in Kensington, London, where Lewis lived, No. 61 Palace Gardens Terrace.[24]

Blue plaque: Wyndham Lewis, 61 Palace Gardens Terrace, London W8

Disquisitional reception [edit]

In his essay "Good Bad Books", George Orwell presents Lewis equally the exemplary writer who is cerebral without being artistic. Orwell wrote, "Enough talent to set dozens of ordinary writers has been poured into Wyndham Lewis's so-called novels ... Yet it would be a very heavy labour to read 1 of these books right through. Some indefinable quality, a sort of literary vitamin, which exists even in a book similar [1921 melodrama] If Winter Comes, is absent from them."[25]

In 1932, Walter Sickert sent Lewis a telegram in which he said that Lewis's pencil portrait of Rebecca W proved him to be "the greatest portraitist of this or any other time."[26]

Anti-semitism [edit]

For many years, Lewis'southward novels have been criticised for their satirical and hostile portrayals of Jews.[ citation needed ] Tarr was revised and republished in 1928, giving a new Jewish character a central office in making certain a duel is fought. This has been interpreted every bit an emblematic representation of a supposed Zionist conspiracy against the West.[27] His literary satire The Apes of God has been interpreted similarly, because many of the characters are Jewish, including the modernist writer and editor Julius Ratner, a portrait which blends anti-semitic stereotype with historical literary figures John Rodker and James Joyce.

A key feature of these interpretations is that Lewis is held to have kept his conspiracy theories hidden and marginalized. Since the publication of Anthony Julius'south T. S. Eliot, Anti-Semitism, and Literary Class (1995), where Lewis's anti-semitism is described equally "essentially piddling", this view is no longer taken seriously.[ according to whom? ]

Books [edit]

- Tarr (1918) (novel)

- The Caliph'due south Pattern : Architects! Where is Your Vortex? (1919) (essay)

- The Fine art of Being Ruled (1926) (essays)

- The Wild Trunk: A Soldier of Humour And Other Stories (1927) (short stories)

- The Panthera leo and the Fox: The Role of the Hero in the Plays of Shakespeare (1927) (essays)

- Time and Western Man (1927) (essays)

- The Childermass (1928) (novel)

- Paleface: The Philosophy of the Melting Pot (1929) (essays)

- Satire and Fiction (1930) (criticism)

- The Apes of God (1930) (novel)

- Hitler (1931) (essay)

- The Diabolical Principle and the Dithyrambic Spectator (1931) (essays)

- Doom of Youth (1932) (essays)

- Filibusters in Barbary (1932) (travel; afterward republished equally Journeying into Barbary)

- Enemy of the Stars (1932) (play)

- Snooty Baronet (1932) (novel)

- One-Mode Vocal (1933) (poetry)

- Men Without Art (1934) (criticism)

- Left Wings over Europe; or, How to Make a War near Nothing (1936) (essays)

- Blasting and Bombardiering (1937) (autobiography)

- The Revenge for Honey (1937) (novel)

- Count Your Dead: They are Alive!: Or, A New War in the Making (1937) (essays)

- The Mysterious Mr. Bull (1938)

- The Jews, Are They Man? (1939) (essay)

- The Hitler Cult and How it Will End (1939) (essay)

- America, I Presume (1940) (travel)

- The Vulgar Streak (1941) (novel)

- Anglosaxony: A League that Works (1941) (essay)

- America and Catholic Homo (1949) (essay)

- Rude Assignment (1950) (autobiography)

- Rotting Hill (1951) (short stories)

- The Writer and the Absolute (1952) (essay)

- Self Condemned (1954) (novel)

- The Demon of Progress in the Arts (1955) (essay)

- Monstre Gai (1955) (novel)

- Malign Fiesta (1955) (novel)

- The Red Priest (1956) (novel)

- The Letters of Wyndham Lewis (1963) (letters)

- The Roaring Queen (1973; written 1936 only unpublished) (novel)

- Unlucky for Pringle (1973) (short stories)

- Mrs Knuckles'due south Million (1977; written 1908–x but unpublished) (novel)

- Creatures of Addiction and Creatures of Modify (1989) (essays)

Paintings [edit]

- The Theatre Managing director (1909), watercolour

- The Courtesan (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

- Indian Dance (1912), chalk and watercolour

- Russian Madonna (besides known as Russian Scene) (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

- Lovers (1912), pen and ink, watercolour

- Mother and Kid (1912), oil on canvas, at present lost

- The Dancers (study for Kermesse) (1912), black ink and watercolour, (paradigm)

- Composition (1913), pen and ink, watercolour, (image)

- Plan of State of war (1913–14), oil on canvas

- Slow Attack (1913–14), oil on canvas

- New York (1914), pen and ink, watercolour

- Argol (1914), pen and ink, watercolour

- The Crowd (1914–15), oil pigment and graphite on sail, (epitome)

- Workshop (1914–xv), oil on sail, (image)

- Vorticist Composition (1915), gouache and chalk, (image)

- A Canadian Gun-pit (1919), oil on canvas, (image)

- A Battery Shelled (1919), oil on sheet, (prototype)

- Mr Wyndham Lewis as a Tyro (1920–21), oil on canvas, (prototype)

- A Reading of Ovid (Tyros) (1920–21), oil on canvas, (epitome)

- Seated Figure (c.1921) (image)

- Mrs Schiff (1923–24), oil on canvas, (epitome)

- Edith Sitwell (1923–1925), oil on sheet, (image)

- Bagdad (1927–28), oil on wood, (paradigm}

- Three Veiled Figures (1933), oil on canvas, (image)

- Creation Myth (1933–1936, oil on canvas, (prototype)

- Red Scene (1933–1936), oil on canvas, (epitome)

- One of the Stations of the Expressionless (1933–1837), oil on canvas, (epitome}

- The Surrender of Barcelona (1934–1937), oil on canvas, (paradigm)

- Panel for the Safe of a Great Millionaire (1936–37), oil on sail, (epitome)

- Newfoundland (1936–37), oil on sail, (image)

- Pensive Head (1937), oil on canvas, (image)

- La Suerte (1938), oil on canvas, (prototype)

- John Macleod (1938), oil on sail (image)

- Ezra Pound (1939), oil on canvas, (prototype)

- Mrs R.J. Sainsbury (1940–41), oil on canvas, (image)

- A Canadian War Factory (1943), oil on canvas, (prototype)

- Nigel Tangye (1946), oil on canvas, (image)

Notes and references [edit]

- ^ The championship is based on a gimmicky all-time-seller, "The English, Are They Human?".

- ^ Grace Glueck (22 September 1985). "Wydham Lewis:Painter, Polemicist, Iconoclast". The New York Times . Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Richard Cork, "Lewis, (Percy) Wyndham (1882–1957)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Printing, 2004.

- ^ "The programme and card from the Cave of the Aureate Calf, Cabaret and Theatre Club | Explore 20th Century London". www.20thcenturylondon.org.u.k..

- ^ "The Art and Ideas of Wyndham Lewis" Archived 5 February 2007 at the Wayback Motorcar, FluxEuropa.

- ^ Terrazas, Melania (2001). "Tragic Clowns/Male Comedians: Wyndham Lewis'southward "Enemy of the Stars" and Samuel Beckett'due south Waiting for Godot". Wyndham Lewis Almanac. 8: 51 – via The Wyndham Lewis Society.

- ^ Paul Gough (2010) 'A Terrible Beauty': British Artists in the Offset Globe War (Sansom and Company) 203–239, ISBN 9781906593001.

- ^ Stephen Farthing (Editor) (2006). 1001 Paintings Yous Must See Before You Dice. Cassell Illustrated/Quintessence. ISBN978-1-84403-563-2.

- ^ Trotter, David (2011) [1999]. "Chapter 3: The Modernist Novel". In Levenson, Michael (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Modernism (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 69. ISBN9781107495708.

- ^ Tyro, scans of the publication at The Modernist Journals Projection website.

- ^ Time and Western Human being, Morató, Yolanda. "Fourth dimension and Western Man". The Literary Encyclopedia. First published 2 March 2005; cf. Edward Chaney, '"Mummy Get-go: Statue After": Wyndham Lewis, Diffusionism, Mosaic Distinctions and the Egyptian Origins of Art,' Ancient Egypt in the Modern Imagination, eds. E. Dobson and N. Tonks (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020).

- ^ Neilson, Brett (1999). "History'south Postage: Wyndham Lewis'south The Revenge for Dearest and the Heidegger Controversy". Comparative Literature. 51 (1): 24–41. doi:10.2307/1771454. JSTOR 1771454 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d e Bridson, D. G. (2014). The Filibuster: A Report of the Political Ideas of Wyndham Lewis. A&C Black. pp. 232–248.

- ^ "Wyndham Lewis "Rotting Hill"". Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved thirteen June 2011.

- ^ Notting Loma history: 5 – Rotting Hill, 1940s (PDF), Kensington & Chelsea Community History Group, archived from the original (PDF) on 31 Jan 2012, retrieved 10 February 2012

- ^ The Human Age. Wyndham Lewis. The Listener (London, England), Thursday, 2 June 1955; p. 976; Issue 1370.

- ^ National Portrait Gallery. "Portrait of Froanna". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ National Portrait Gallery. "Froanna – Portrait of the Artist's Wife". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ a b David Trotter (23 Jan 2001). "A most modern misanthrope: Wyndham Lewis and the pursuit of anti-pathos". The Guardian / London Review of Books . Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ^ Time and Tide, 2 March 1935, p. 306.)

- ^ Bête Noire or Scapegoat? Yolanda Morató (2010) Bête Noire or Scapegoat?, European Journal of English Studies, 14:three, 221–234, DOI: x.1080/13825577.2010.517291

- ^ Wyndham Lewis – 1882–1957: Fundación Juan March, Madrid

- ^ Nasher Museum Archived 8 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 17 September 2010

- ^ "LTM Recordings | Independent Record Label | Official Website".

- ^ "Wyndham Lewis blue plaque". openplaques.org. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Fifty Orwell Essays, A Projection Gutenberg of Commonwealth of australia eBook

- ^ Campbell, Peter (11 September 2008). "At the National Portrait Gallery". London Review of Books, p. 12.

- ^ Ayers, David. (1992) Wyndham Lewis and Western Man. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan.

Further reading [edit]

- Ayers, David. (1992) Wyndham Lewis and Western Homo. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan.

- Chaney, Edward (1990) "Wyndham Lewis: The Modernist every bit Pioneering Anti-Modernist", Modernistic Painters (Fall, 1990), 3, no. 3, pp. 106–09.

- Edwards, Paul. (2000) Wyndham Lewis, Painter and Author. New Oasis and London: Yale U P.

- Edwards, Paul and Humphreys, Richard. (2010) "Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957)". Madrid: Fundación Juan March

- Gasiorek, Andrzej. (2004) Wyndham Lewis and ModernismWyndham Lewis and Modernism. Tavistock: Northcote House.

- Gasiorek, Andrzej, Reeve-Tucker, Alice, and Waddell, Nathan. (2011) Wyndham Lewis and the Cultures of Modernity. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Grigson, Geoffrey (1951) 'A Main of Our Time', London: Methuen.

- Hammer, Martin (1981) Out of the Vortex: Wyndham Lewis every bit Painter, in Cencrastus No. 5, Summer 1981, pp. 31–33, ISSN 0264-0856.

- Jaillant, Lise. "Rewriting Tarr Ten Years Later: Wyndham Lewis, the Phoenix Library and the Domestication of Modernism." Journal of Wyndham Lewis Studies 5 (2014): ane–30.

- Jameson, Fredric. (1979) Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as Fascist. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press.

- Kenner, Hugh. (1954) Wyndham Lewis. New York: New Directions.

- Klein, Scott Westward. (1994) The Fictions of James Joyce and Wyndham Lewis: Monsters of Nature and Design. Cambridge: Cambridge Academy Press.

- Leavis, F.R. (1964). "Mr. Eliot, Mr. Wyndham Lewis and Lawrence." In The Common Pursuit, New York University Press.

- Michel, Walter. (1971) Wyndham Lewis: Paintings and Drawings. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Meyers, Jeffrey. (1980) The Enemy: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis. London and Henley: Routledge & Keegan Paul.

- Morrow, Bradford and Bernard Lafourcade. (1978) A Bibliography of the Writings of Wyndham Lewis. Santa Barbara: Blackness Sparrow Press.

- Normand, Tom. (1993) Wyndham Lewis the Artist: Holding the Mirror upwardly to Politics. Cambridge. Cambridge University Printing.

- O'Keeffe, Paul. (2000) Some Sort of Genius: A Biography of Wyndham Lewis. London: Cape.

- Orage, A. R. (1922). "Mr. Pound and Mr. Lewis in Public." In Readers and Writers (1917–1921), London: George Allen & Unwin, Ltd.

- Rothenstein, John (1956). "Wyndham Lewis." In Modernistic English Painters. Lewis To Moore, London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

- Rutter, Frank (1922). "Wyndham Lewis." In Some Gimmicky Artists, London: Leonard Parsons.

- Rutter, Frank (1926). Evolution in Modern Art: A Study of Mod Painting, 1870–1925, London: George G. Harrap.

- Schenker, Daniel. (1992) Wyndham Lewis: Religion and Modernism. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama Press.

- Spender, Stephen (1978). The Thirties and Subsequently: Poetry, Politics, People (1933–1975), Macmillan.

- Stevenson, Randall (1982), The Other Centenary: Wyndham Lewis, 1882–1982, in Hearn, Sheila G. (ed.), Cencrastus No. x, Autumn 1982, pp. 18–21, ISSN 0264-0856

- Waddell, Nathan. (2012) Modernist Nowheres: Politics and Utopia in Early on Modernist Writing, 1900–1920. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wagner, Geoffrey (1957). Wyndham Lewis: A Portrait of the Artist as the Enemy, New Oasis: Yale University Printing.

- Woodcock, George, ed. Wyndham Lewis in Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Publications, 1972.

External links [edit]

- 36 artworks by or subsequently Wyndham Lewis at the Art Great britain site

- ""Long Live the Vortex!" and "Our Vortex" (1914) by Lewis at the Verse Foundation

- Website of the Wyndham Lewis Society

- Biography of Wyndham Lewis at Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery, London.

- "Time and Western Man" essay from Yale

- "Cocky Condemned," essay about Lewis and Canada in The Walrus, October 2010

- "The Enemy Speaks" audiobook CD by Lewis

- Works by Wyndham Lewis at Faded Page (Canada)

- Wyndham Lewis Collection at the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

- Wyndham Lewis's Art Drove at the Harry Ransom Eye at The University of Texas at Austin

- Wyndham Lewis collection at University of Victoria, Special Collections

- Art and Literary Works by Wyndham Lewis from the C. J. Fox Collection at University of Victoria, Special Collections

- Wyndham Lewis Drove (archival) and (book collection) at Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections at York University

woolcockyousagannot.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wyndham_Lewis